Anastasia Pavlou understands her artistic work as one that can be perceived as context-related in installed form in exhibitions, thus enabling her to create an expanded aesthetic space of experience. Pavlou’s paintings, which take their cues from Art Informel, are both tightly organized and remarkable for the transparency and expansiveness of their pictorial space. They come across as works that were created spontaneously but developed slowly. Her autonomous, small-format drawings, meanwhile, are a form of figurative, inspired visual thinking. We encounter them again, scaled up, on canvases in her exhibitions. Pavlou favours a perception of works of art that the British philosopher Richard Wollheim in 1980 described as a “seeing-in” as opposed to the representational seeing, or “seeing-as,” that in contemporary art has since become the norm. “Seeing-in,” unlike the more direct “seeing-as,” “permits unlimited, simultaneous attention to what is seen and to the features of the medium,” writes Wollheim. It is this material aspect of art to which the artist, in her current works, directs our attention.

Anastasia Pavlou describes her exhibition in Amden as a prologue to an exhibition in Athens. Repetition and continuation are thus two keywords that describe the planned process. With the exception of a small self-portrait, all of the works on display in Amden were generated during a stay on site. Reflections on the function of performative processes in the making of an exhibition and on what the French artist Pierre Huyghe called the “temporalization of the exhibition” play an important role for Pavlou in Notes and Counter Notes on the Light that Burns. The aim of her presentation in Amden was to create a connection to the exhibition space and the region and to understand how these contribute to the creative process. The artist writes that she tried to do two things at once: “to close my eyes to the possible forms that can emerge until I reach Amden, and to allow the environment and the place to set the creative process in motion once I am physically there, and at the same time to put myself in a mental process in which I can imagine how something can begin in Amden and end in Amden.”

Exhibited works:

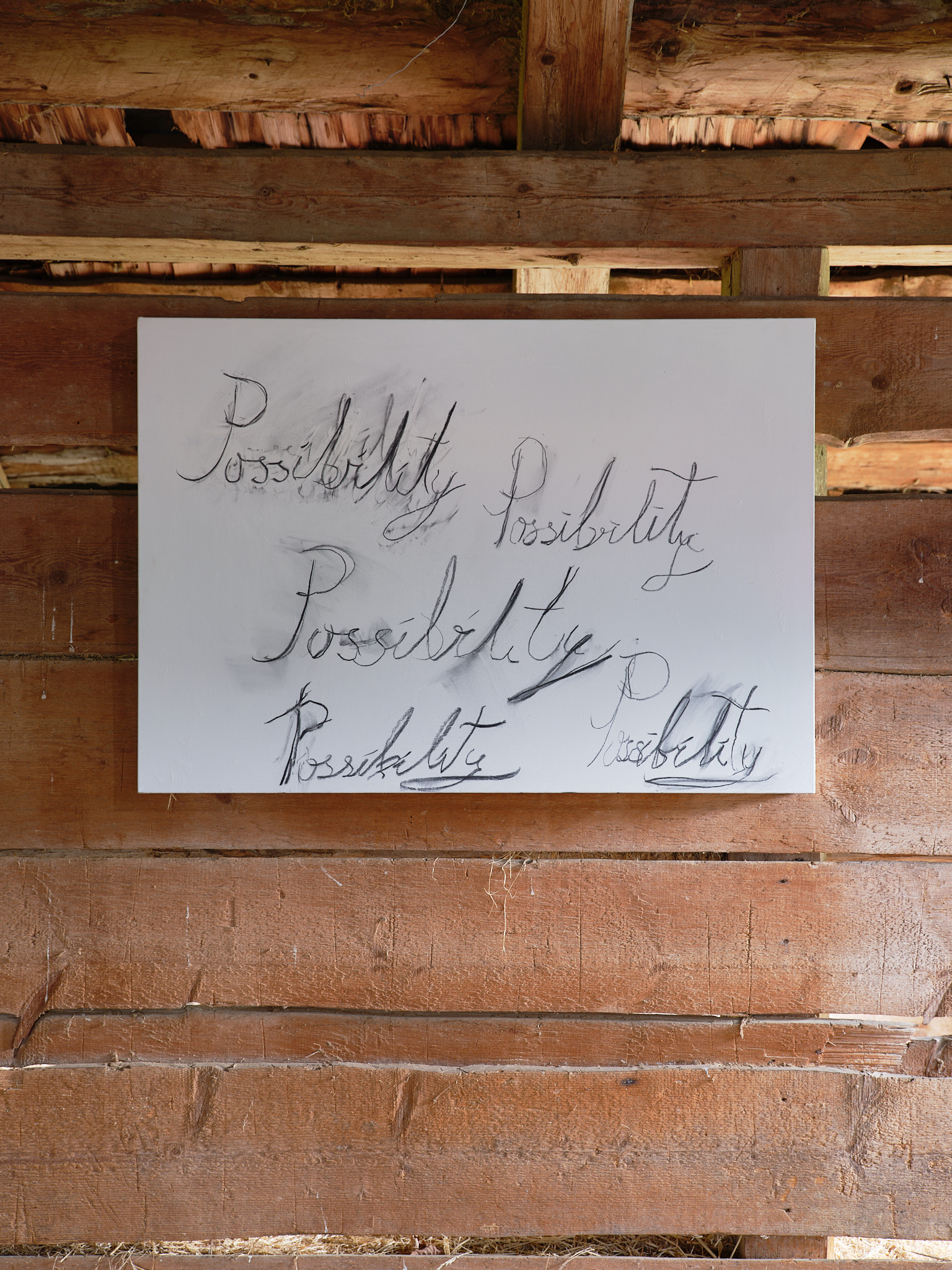

Anastasia Pavlou

Thought’s Real Glow, 2025

Gesso and charcoal on canvas, 200 x 200 cm

Anastasia Pavlou

The Dreamer Dreams, 2025

Gesso and charcoal on canvas, 70 x 100 cm

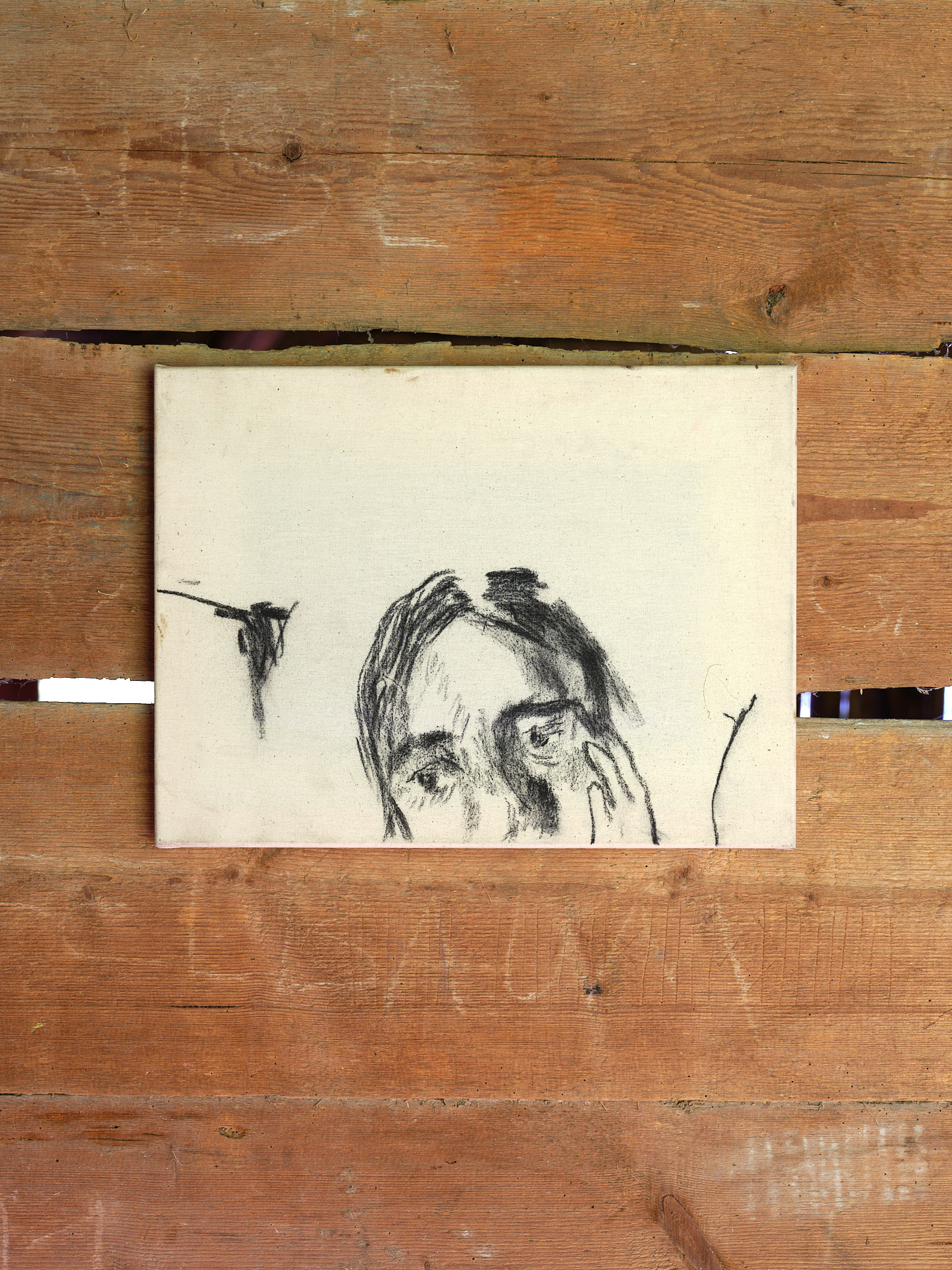

Anastasia Pavlou

Self Portrait (1), 2025

Gesso and charcoal on canvas, 30 x 40 cm

«... one only receives comfort from the fire when one leans his elbows on his knees and holds his head in his hands. This attitude comes from the distant past. The child by the fire assumes it naturally. Not for nothing is it the attitude of the Thinker. It leads to a very special kind of attention which has nothing in common with the attention involved in watching or observing. ... When near the fire, one must be seated; one must rest without sleeping.» (Byung-Chul Han, “Vita Contemplativa”, 2022)

In contrast to the presentation in Amden, which exclusively featured works based on drawing or writing and was staged like a performance, the classically hung exhibition 'The Light that Burns' at the Hot Wheels Athens gallery (17 September to 7 November 2025) was dominated by collaged material images. These works are characterised by the visual opacity of their multi-layered surfaces, into which the artist has incorporated various materials and different dyes. Pavlou thus lends the paintings the quality of objects. In Athens, standing before the originals, the painted surfaces of the horizontally painted canvases in muted colours reminded me of the multi-layered sealed surfaces in public spaces. One could also speak of images that, like those of the Nouveaux Réalistes in the 1960s, deal with urban nature. Pavlou speaks of 'The Light that Burns' as an exhibition of paintings that explores the act of making and the conditions that shape it as an event in space. The title of the exhibition is taken from the book of the same name, a collection of poems by the Greek poet Kostas Varnalis, first published in 1922.

–– Roman Kurzmeyer

Images

Images

Info

Info

anastasiapavlou.com

anastasiapavlou.com